The Gryning | Essays

“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” – Ecclesiastes.

The Gryning | Essays applies this principle to the subject of credit bubbles. Where I chronicle the collapse of the current, global credit bubble – the largest and broadest in history – analyzing current events from the perspective of Austrian economics and placing them in historical context.

For a comprehensive understanding of the major talking points in the world of finance this year, click below.

9 essays for $8.99 - for $1 per essay, you get a stocking filler giving you a deeper understanding of the financial landscape.

For a sample, below is an essay from November 2021 (this is not included in the above offer).

Policy Error - November 20, 2021

It wasn’t supposed to happen like this. Market commentators and bank analysts assured us that we were following the 2008–2013 template. A panic, followed by central bank intervention, then a credit-fueled recovery. Gold investments—antisocial by their nature—do well during the uncertainty following the panic but then fade as normality returns. After all, gold has no yield, so the thinking goes.

2020 was dissimilar to 2008. It wasn’t capital-intense industries that suffered because of overcapacity in 2020; it was small businesses that were shut down and now can’t find workers or inputs. The Fed again used its money-printing powers to recapitalize banks, but this time the greater effect was to fund transfer payments to individual consumers. When the economy reopened, the surge of bank-finance capex that followed 2009 intervention was replaced by a surge of consumer spending interacting with fewer goods. Who could be surprised by surging inflation?

Economists, politicians, and journalists, apparently. Fed chairman Jerome Powell, for example, in April 2020, after his policies had been implemented, said:

“Back 12 years ago, when the financial crisis was getting going and the Fed was doing quantitative easing, many people feared that the increases in the money supply, as a result of quantitative easing asset purchases, would result in high inflation. Not only did it not happen, the challenge has become that inflation has been below our target. So that is— globally the challenge has been inflation below target. Honestly, it is not a first order concern for us today that too high inflation might be coming our way in the near-term. Far from it.”

Fed minutes record that the economist staffers at the Fed as late as March 2021 were worried that “underlying inflationary pressures remained subdued.” By June, Powell could not no longer ignore the surge in consumer prices, but he argued the increase was from short-term transitory factors involving production bottlenecks. On November 8, Powell retreated further, saying: “Transitory is a word that people have had different understandings of.”

The Biden regime is, of course, scrambling to shift responsibility for the surge in inflation, blaming rising prices on the rapacity of corporations: “That’s why the BidenHarris Administration is taking bold action to enforce the antitrust laws” (similarly, in the midst of the 1970s inflation, Gerald Ford called for the maximum fine on antitrust violations to be raised from $50,000 to $1 million). Biden himself at a recent press conference blamed;

first, supply chain mismanagement,

second, Russia and OPEC for not pumping more oil,

third, he claimed that wages are rising faster than prices.

This latter claim is what Biden-regime apologists have latched on to. MSNBC, for example, ran a column pointing out that “Even though millions of Americans lost their jobs, enhanced unemployment benefits and stimulus payments left many of them better off, not worse. . . . The result of all this was that Americans ended 2020 $13.5 trillion richer than they were at the beginning of the year . . . the bottom 25 percent of income earners had 50 percent more in their checking accounts in October 2020 than they did a year earlier.” Inflation is, therefore, “the predictable product of the economy’s rapid recovery, and its costs have been offset, to a large degree, by robust wage growth and government policies.”

The problem with this narrative is that it violates Say’s Law, which instructs that we don’t really buy things with money: first we trade our productions for money, and then we use that money to buy the things we want; so it is really with our productions that we buy things.

Say’s Law must always be true in aggregate (overall consumption cannot exceed production), but unsound money can falsify Say’s Law for the individual by introducing the Cantillon Effect. Richard Cantillon pointed out that those sitting near emissions of newly printed money (bankers, for example) can demand goods from others before prices have risen. Those who get the new money last (typically laborers) have to pay the higher prices before their incomes increase. Total consumption still equals production, but consumption is shifted from producers to financial operators.

The Cantillon Effect has for decades operated to concentrate wealth in the U.S., but it has also operated to shift consumption to America from the rest of the world. The rising cash balances and incomes trumpeted by Biden and his media apologists is not due to additional productivity but, they admit, comes from money printing. Demand for goods from China has surged, leading (in part) to the supply chain mess. Chinese sellers get these newly printed dollars and use them to buy new inputs, and that’s when they discover that their productions—sold for dollars—will not buy a commensurate amount of new inputs. They must raise their prices, and the new money bids up input costs substantially—the reason that commodity prices are surging.

An inflection point has now been reached whereby inflation is rising faster than American wages: nonfarm employees have seen their wages increase 4.9% over the past year while CPI inflation has increased 6.2% (and real inflation is far higher).

The cure for high prices is high prices, so the saying goes, and falling real incomes are now forcing Americans to alter their buying expectations, as very ugly University of Michigan surveys make clear.

Wouldn’t it be ironic if all of those containers stuck on cargo ships anchored outside of Los Angeles arrived a few months from now right as consumers run out of money and go on a buyers’ strike. One economist, David Blanchflower of Dartmouth and formerly a member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, argues that these surveys suggest that the U.S. is already in recession, potentially worse than 2008.

This is the box the Fed finds itself in. Printing money as prices surge is madness, but raising rates to contain inflation will tighten financial conditions and hit Americans’ purchasing power even further. There is chatter the Fed is making the same policy mistake as in 2008, when $150/bbl oil panicked the Fed into tightening right as the economy was entering a death spiral.

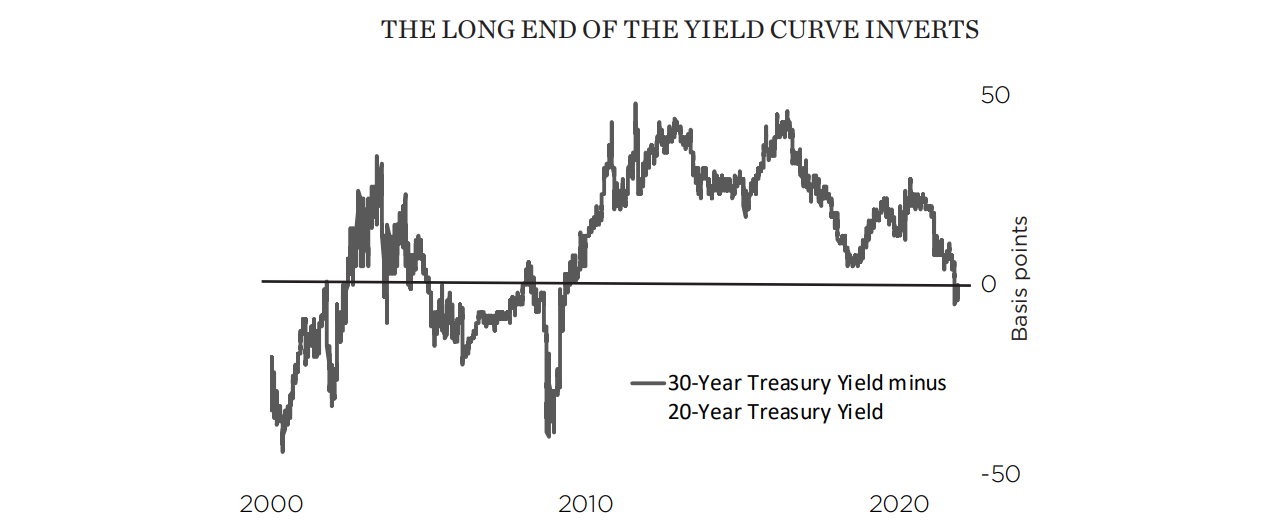

The bond market seems to agree. Whereas the Fed controls short rates with an iron fist, the market has more sway over longer-term Treasuries. The chart below shows the spread between the yield on the 30-year Treasury bond versus the 20- year Treasury bond. The long-end of the yield curve steepened dramatically during the credit mania following the 2000 crash and the 2008 crash; whereas, the curve is plunging currently. The Fed is going to tighten into this?

Market expectations were that the Fed taper would be the nail in the coffin for gold. Gold and gold mining stocks have, instead, surged. It seems that the yellow metal agrees with bonds that the Fed’s tightening will lead to market conditions that will force additional money printing and in the not distant future. Those who have not lived through or studied high-inflation economies forget that price increases are not smooth but become increasingly volatile as they go higher. With the progressives having gained power through Biden, it’s a good bet that after the next crash the next QE will again be directed toward consumers—the second wave of inflation will be worse and will probably bring with it price controls and more shortages. Best to stock up before others start hoarding.

If you found value in the above essay, then consider picking up The Gryning | Essays below:

If Repeatable processes and frameworks are your thing: Models, frameworks, and exhaustive research, then join my premium service below:

If you know anyone that may benefit from this free publication, please share the note with them: