We had two key events last week that triggered a Monday market meltdown.

First, the European Central Bank announced the end of QE (and the liftoff of interest rates next month).

Second, the May U.S. inflation report showed no sign of slowing in the rate-of-change of prices.

The latter underscores the monetary policy regime change that's underway in the U.S. (from easing/pumping liquidity to tightening/extracting liquidity). In short, the liquidity spigot that has come from the two biggest economies in the world (the U.S. and the euro area), for the better part of the past 14 years, has been closed.

That said, this coming regime change has been well telegraphed, with some of the bubbles from the excesses of the era having been pricked.

What is now being contemplated, is maybe the biggest bubble of them all - the government bond market.

As we discussed last week, with the end of QE in Europe, the sovereign debt buyer of last resort, particularly debt of the fiscally fragile countries in the eurozone, will soon be out of the market. In the U.S., the Fed is no longer buying Treasuries.

Conversely, as of June 1st, they are selling Treasuries.

With the exit of this life-line-like bond market demand, this all seems like a formula for a sharp fall in bond prices, which would translate into a shock in market interest rates (i.e. spike). That's precisely what it looked like yesterday - the U.S. 10-year yield spiked 29 basis points - a huge one-day move, the biggest since March 2020.

We talked quite a bit last week about two very vulnerable sovereign debt markets in Europe - both Italian and Spanish yields spiked too (up 20 and 25 basis points, respectively). When yields for both Italy and Spain were around 7%, back in 2012, they were on default watch. Should the current pace of these bond yields continue, we could revisit that danger zone by this summer.

Let’s keep in mind, the debt load for each is greater now than it was back in 2012 - therefore, the unsustainability of the debt service burden would trigger at even lower yield levels now.

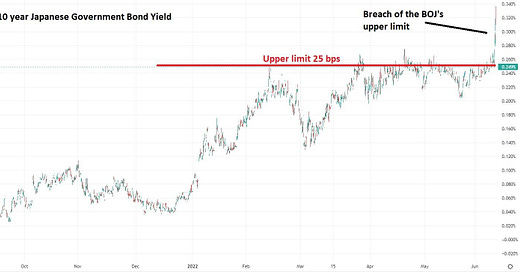

Now, with all of this said, what was the most troubling market observation of the day? The Japanese government bond market - the 10-year JGB did this...

Remember, the Bank of Japan is still in full quantitative easing mode. In fact, not only are they buying JGBs, under their "yield curve control" program, they are managing the yield curve, and doing so by manipulating the 10-year yield.

They are targeting 0%, allowing 25 basis points on either side. As you can see in the chart above, that top limit breached. This created some speculation that the BOJ might be fighting off speculators (and losing), or perhaps considering an increase in the band (to plus/minus 50 bps).

In the end, the yield came quickly back into line (within the limit). What does this all mean? It's a reminder that, not only is the Bank of Japan (BOJ) still in the QE business, but they are in the unlimited QE business. To defend the top limit of their yield target, they become buyers of unlimited Japanese Government Bonds. They have a stated policy to buy as much as they see fit - in Japan, that also means buying stocks, real estate, corporate bonds, foreign assets - it's all fair game.

With that in mind, we shouldn't underestimate the appetite of global central banks to coordinate, to keep key global interest rates in check. That includes U.S. Treasuries, and European sovereign debt.

As I said in my April 29th note:

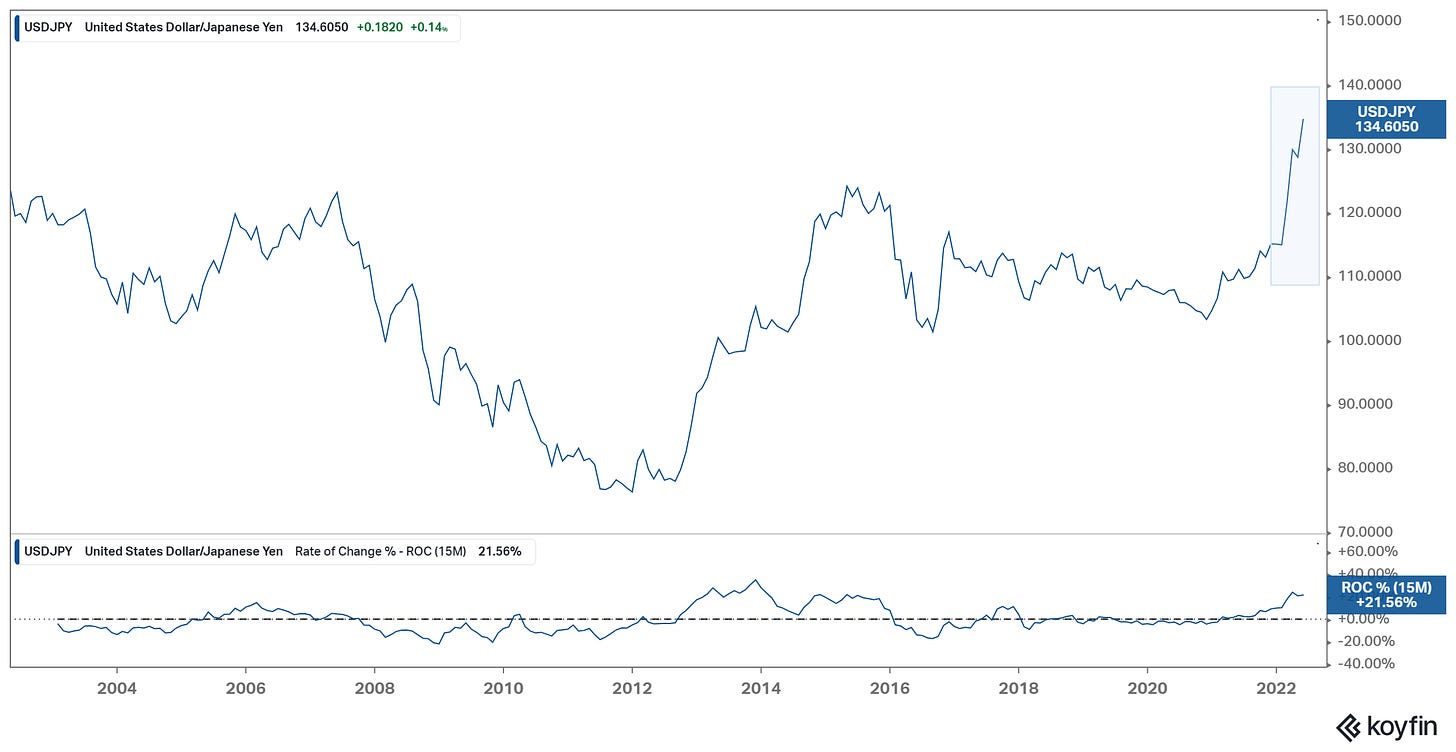

“How do you prevent a global economic shock that may (likely) come from reversing the mass liquidity deluge of the past two years (if not 14 years, post Global Financial Crisis)? You keep the liquidity pumping from a part of the world that has a long-term structural deflation problem, and that has the biggest government debt load in the world (exception, only Venezuela).

The Bank of Japan, in this position, can be buyers of foreign government debt (namely the U.S.) to keep our market rates in check (keeps the world relatively stable), which gives the Fed breathing room on the rate hiking path.

Japan's benefit? The world gives Japan the greenlight to devalue the yen, inflate away debt and increase export competitiveness (through a weaker currency) - they hit the reset button on an unsustainable, debt-laden economy”.

So, what's going on with the yen? It has been devaluing (blue box in chart below), rapidly (24-year low)...