The September inflation came in hot (more in a moment).

Stocks went down. Yields went up. Then it all reversed.

Once again, the 4% area in the 10-year yield, the benchmark of the government bond market, seems to be the line in the sand.

As we've discussed often in my daily notes, this liftoff phase of global interest rates, where central banks have been exiting emergency policies, has been led by the Fed - a rise in U.S. rates, moves the anchor for global interest rate.

With that, as the U.S. 10-year yield hit 4% in late September, it dragged higher government bond yields, and it resulted in a shock in the UK government bond market, which required intervention from the Bank of England.

The inflation data for September was hotter than expected, and the 10-year yield had a quick visit to 4% and reversed. Stocks reversed as well, and that turned into another historic moment for the stock market. Remember, last week, we saw one of the biggest two-day gains in stocks and I presented the chart below:

Looking back through all of the two-day returns in the S&P 500 futures, dating back to 2006, a two-day return of over 5% is rare, and every time since 2006, it has been fueled by policymaker intervention, to respond to a significant risk to, or destabilisation of, the global financial system. These were all significant moments in the history of markets.

As such, the big 5%+ bounce in stocks last week was (also) intervention-driven, as the Bank of England intervened in the UK bond market to stabilise the UK financial system. Again, given the comparables in history, we can draw the conclusion that this UK bond market event was a very significant threat to the global financial system.

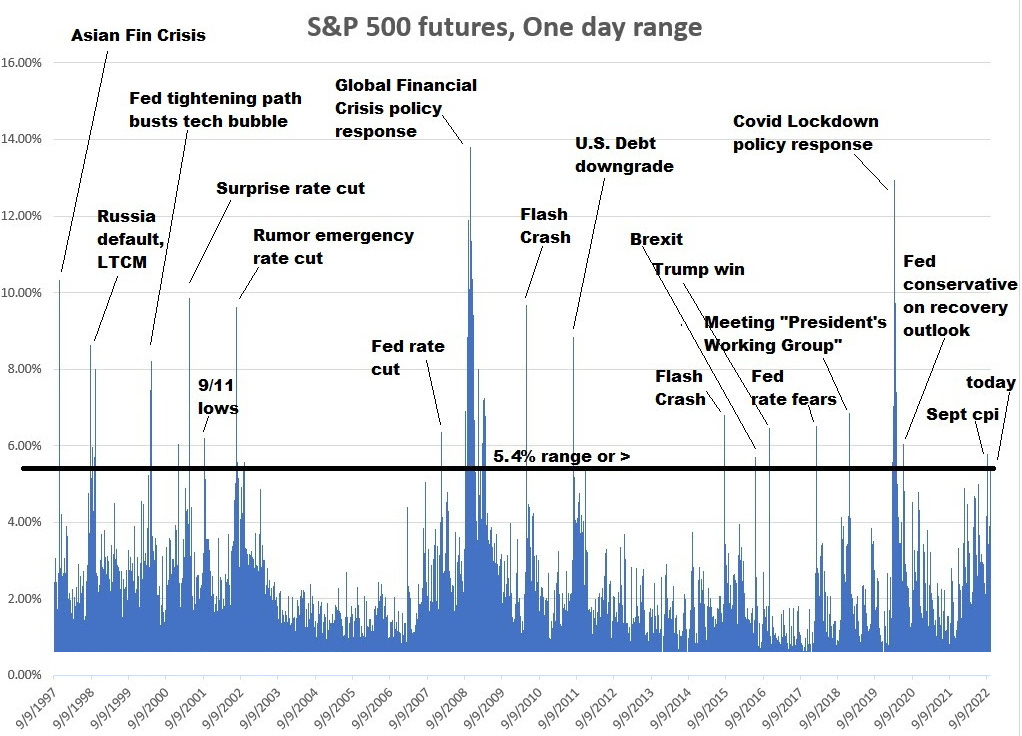

Now, let's fast forward to today, and again we have another rare occurrence. The S&P futures plunged 2.6% after the inflation data, and then surged to close up over 2% for the day. It was on a 5.4% trading range.

I went through 25 years of S&P futures data that have this magnitude of trading range, or greater in common. And like the two-day return study, these extraordinarily large trading range days (finishing up or down) also come associated with very significant moments.

As you can see in the chart above, these ranges are associated with major market crises, policymaker intervention, policy change (via elections/votes) and market liquidity crises.

The past two, however, have come as the result of an inflation report (and have come in consecutive months)!

What do we make of it? High inflation environments, historically, have only been resolved when short term rates (the rates the Fed sets) are raised above the rate of inflation. The Fed remains well below the rate of inflation.

Why? As we've discussed along the way of this Fed tightening path, even if the U.S. economy (including the government's ability to service its debt) could withstand the pain of high interest rates, the rest of the world can't. We're already seeing, at current interest rate levels, that the global financial system can't withstand it.

That's why this 4% level in the 10-year yield seems to be a vulnerable point. And that's why this inflation report has become the equivalent of a major market moment in recent history.

The good news, as we discussed yesterday, some of the hot spots in the inflation report, are cooling (new cars and rents), though it didn't show in yesterday’s report. In fact, even if prices continued to move at the pace of the past three months (the three-month average monthly headline inflation) we're looking at an inflation rate that is running around 2% annualised -- which is the Fed's inflation target.

And if that's the case, we could be looking at a collapse in inflation by next year, as most of the effect of the 300 basis points of tightening has yet to be felt in the economy (still lagging).

So, how would 2% inflation be possible (much less lower), if the Fed Funds rate is still (at the moment) well below the 8.2% current annual inflation rate that we see in the media reports (which measures prices now against prices of a year ago)?

Arguably, the Fed has done its job, slowing the economy and lowering inflation (which is showing up in the monthly inflation change). They've done it by destroying confidence and destroying stock market wealth. And that's been accomplished mostly through tough talk.

Why is that good news? Perhaps the pain has already been inflicted, on the stock market and the bond market.

PS: If you think someone will benefit from reading this publication, please pass this along.