Nothing Ever Happens

The S&P 500 slipped 0.2% on Friday, its third straight loss, while the Nasdaq fell 0.5% and the Dow added 35 points as investors weighed the prospects of Federal Reserve rate cuts against rising geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Fed Governor Waller’s suggestion that rate cuts could arrive as early as July contrasted sharply with Chair Powell’s more cautious, data-dependent stance.

Geopolitical uncertainty deepened after President Trump delayed a decision on potential US military involvement in the Israel-Iran conflict, even as Israel intensified its strikes on key Iranian targets. A 1-pager on the Straight of Hormuz is attached at the end of today’s post.

Friday’s “triple witching” expiration added volatility, prompting a rebound in shorter-dated Treasuries and driving two-year yields down four basis points.

The Global Trend Report (~450 assets & ~850 single stocks) gives you an actionable overview of emerging trends and growing market instabilities.

New Macro Perspectives Structure - we will begin each week with a slightly longer weekly commentary, allowing you to follow the broad strokes of the financial market on a weekly basis. Macro Perspectives for the rest of the week will remain unchanged as I try to make sense of the financial markets with a daily 2 minute read.

Three Things

Too Late Jerome?

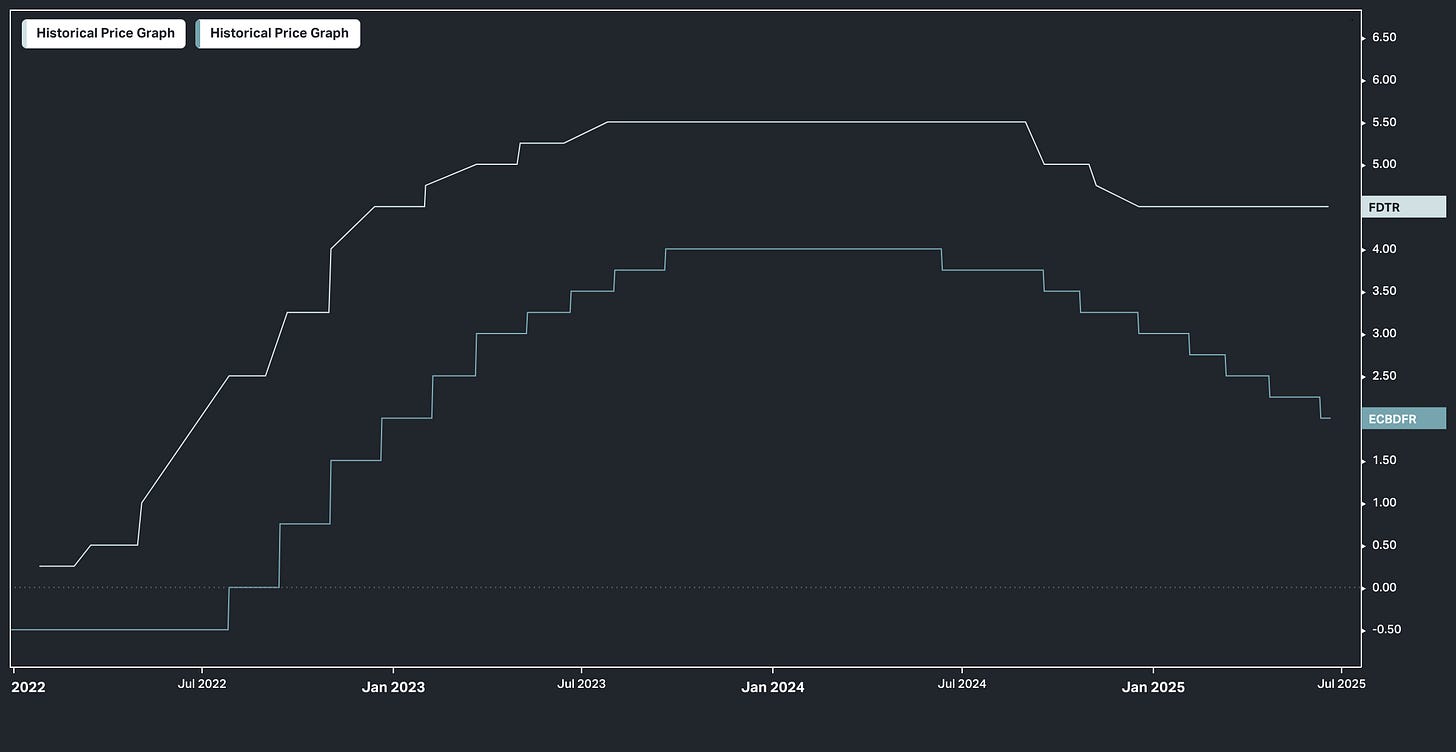

Wednesday’s Fed meeting was mostly uneventful. They downgraded their economic outlook marginally and raised inflation expectations slightly. There was an immediate response of “stagflation is coming”, which I still find silly. The Fed projects 1.4% economic growth and 3% inflation - this is not stagflation. Stagflation is stagnant growth and high inflation. Nominal GDP is expected to be about 4-5% in this scenario. And PCE inflation has averaged 3.3% since 1960. We do not have high inflation any more. And we don’t even have stagnant growth. We have very average inflation right now. Perhaps a bit on the low side. And we have low GDP, not stagnant GDP. So no, this still isn’t a stagflationary environment, but the Fed seems overly concerned about something resembling that. And because of this it looks like they’re starting to fall behind the curve a bit here, assuming the European Central Bank (ECB) is ahead of the game here

One person who clearly agrees with this view is Donald Trump, who didn’t think the Fed decision was at all uneventful. He took to his social media platform to blast Powell:

“Too Late—Powell is the WORST. A real dummy, who’s costing America $Billions! ‘Too Late’ Jerome Powell is costing our Country Hundreds of Billions of Dollars. He is truly one of the dumbest, and most destructive, people in Government, and the Fed Board is complicit. Europe has had 10 cuts, we have had none. We should be 2.5 Points lower, and save $BILLIONS on all of Biden’s Short Term Debt. We have LOW inflation! TOO LATE’s an American Disgrace!”

Not very nice! But I don’t think he’s totally wrong here. There’s a very reasonable argument that the Fed should be loosening here. We have benign inflation and there are enough cracks in the labour market that you could be loosening policy slowly. But Trump didn’t do himself any favours with all this tariff uncertainty, and that’s ultimately what the Fed is worried about now. The last thing they want to see is a material flow-through from tariff price hikes. I don’t think that’s a significant risk, but I can see the argument there so while I lean towards cutting, I can also see the rationale for sitting tight.

In any case, I am not sure how much any of this matters at this point. I’ve long been on the record saying that Trump will appoint a yes-man in 2026 and the job interview for the next Fed Chair is basically going to come down to whether that person will advocate strongly for cuts. So you have to think the probability of the Fed catching up with the ECB will rise as we get into 2026. That’s especially true if the labour market continues to soften.

Nothing Ever Happens.

This is essentially another way of saying “stocks only go up”. That is, even though it seems like lots of stuff happens in the economy, nothing is really happening that the markets care about too much. In just the last few years we’ve had the big Covid scare, the bank panic, the tariff scare and now the WW3 scare with Iran. But if you’d slept through it all and looked at stock prices, you might think that nothing actually happened, as markets have largely shrugged this off.

And that’s all very true at a macro level, but it’s not quite so true at a micro level. The way I would describe most of this is that the financial markets and the economy are primarily dictated by huge secular trends. Those secular trends sometimes get knocked off course temporarily, but those secular trends generally reassert themselves. For example, the biggest macro trend of them all is that human beings like to make progress. Every single day there are billions of humans waking up trying to solve problems and push forward through life. Betting against this is trying to swim against a raging river current. Good luck betting against human progress in the long run. This is the most powerful secular trend that pushes stock prices up over the long-term.

That said, it doesn’t mean nothing ever happens. In fact, one of the reasons I love financial markets is because something happens every day. And even though most of it doesn’t impact our portfolios in a manner that requires big shifts, it is still interesting in the micro sense.

A whole heckuvalot has happened in forex markets this year. In fact, I’d argue that’s been the epicenter of the biggest trades this year. The US Dollar Index is down 7%, which is a pretty big move in just 6 months. But what’s more interesting about this is the knock-on effect to other instruments. For example, foreign stock are up 14.5% this year while US stocks are up just 1.6%. So yeah, it might look like the tariffs did nothing, but in reality they helped contribute to a double-digit outperformance of foreign stocks vs domestic stocks because the tariff policies have directly hurt the USD. So, even though it might look like nothing has happened on an absolute basis, a lot has happened on a relative basis.

Will “Nothing Happen in the Future?”

The “nothing happens” narrative is interesting because it strikes me as something that’s indicative of the times. We have been in a stock market environment where everyone just assumes stocks only go up. And yes, that’s mostly true. But it’s not the direction of stocks that typically concerns me, but the path they take to getting there. There’s been a lot of chatter in recent years about high valuations and future returns. We know that current valuations are a poor predictor of short-term returns, but are typically a good predictor of future 10 year returns. But again, it’s not the direction of the returns that concerns me. If we think of this within a defined duration model then global stocks are about an 18-year instrument at present. US stocks are an even longer instrument at about 23 years if we assume lower expected returns. But over most rolling 10-year time horizons, the stock market will pretty reliably generate positive returns. How positive? Well, we don’t know. But again, the directionality over 10-year time horizons is highly probable to be positive over that long of a time horizon. But the path to getting those positive returns varies significantly. And high valuations are very consistent with worse future risk-adjusted returns. In other words, you might not get lower returns, but you will very likely get bumpier returns, which means more uncertainty of returns.

As a simple heuristic, the 10-year time horizon is pretty close to what an aggregate stock/bond index is. It’s close to the total market portfolio, so it’s the time horizon that the average investor holds in a diversified portfolio (if global stocks are an 18-year instrument and bonds are a 6-year instrument, then a 50/50 portfolio is about 11.5 years). And that makes it the most important portfolio in many ways. But it’s also the most confusing portfolio for us to match to our liabilities because it’s the in-betweener portfolio. It’s not short enough like cash, where we can definitively match a cash asset with a short-term liability like T-bills. And it’s not long enough where we can just match a long-duration instrument to it and ignore it like we can with stocks (anyone with a 20 year time horizon, eg, can pretty reliably invest in stocks and just ignore them for a long time). That 10-year time horizon is a sort of financial planning no man’s land. Which is why the path to generating stable returns over this period is so important – it’s the portfolio that is most behaviourally challenging in my experience.

And what does the data say right now? It says that current valuations are highly consistent with low risk-adjusted returns, and since stocks are the main contributor to 10-year volatility in the global market portfolio, it makes this an especially tricky time horizon for financial planning needs. And that’s important because it means that even if we can expect positive future returns over the coming 10 years, the path of those returns is likely to be highly uneven because the expectations for high returns and “nothing to happen” is high. And that’s why diversification is more important than ever for anyone who has a multi-temporal set of financial planning needs.

In other words, I expect a lot to happen in the coming 10 years. And much of it will be surprising, which is why stock returns will be more volatile than usual.

If you want take advantage of “a lot of things happening”, subscribe to our Global Trend Report - an information package built to identify market turning points. If you’re passionate about the markets, become an ‘institutional’ member to have daily diagnostics on 100 tickers of your choice.

Hormuz: Strategic Risk and Energy Market Implications