“Money is gold and nothing else,” observed J.P. Morgan in 1912, meaning nothing else is money. Everything else is credit.

Gryning Essay’s is a thought series on an attempt to look at the financial markets through the perspective of Austrian Economics. You can access these essay’s as part of your Investing by Design membership.

The principles of liquidity deduced by Carl Menger mandate that money be the most liquid commodity, that is, the one with the least amount of transaction costs both in time and through time. Money thus began as grain and cattle, then as copper, then silver, then gold. And there it ends. There is no element that has greater liquidity.

The story of liquidity does not end with gold, however. Fully reserved banknotes improve liquidity further by eliminating the need to weigh gold for quantity and assay it for quality, as long as the market has trust in the issuing institution—this is why every great banking system begins with banknotes fully redeemable into gold.

Gryning Essays have discussed at length in previous notes the inevitable corruption of banking: after its proper function of liquefying gold and monetising commercial bills, activities that the free market supports, legal tender laws arrive and allow banks to monetise assets, then debt, then debt of ever greater quantity and ever worse quality.

Assets on The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet

In 1958, economist Melchior Palyi, advisor to the post-hyperinflation Reichsbank, warned Americans not to follow the Weimar Germany path: “When the national credit and the national currency are ‘tapped’ in order to maintain ‘full employment,’ full employment might be maintained. The money market can be kept liquid indefinitely if the Treasury prints certificates and the Federal Reserve monetises them. But what happens to the liquidity of the monetiser?”

A healthy institution—be it a company, a bank, or a central bank—can intervene in the market to support the price of its liabilities. If its liabilities fall in price below fair value, the entity can sell liquid assets to generate cash and then use that cash to purchase and retire its own liabilities at a discount, thus earning a profit to provide the public service of stable prices. Once an entity is illiquid, however, there is nothing it can sell to support the price of its liabilities; sudden sales of illiquid assets result in steeply discounted prices, by definition. The situation is worse if the assets are also of uncertain value.

This is where the Federal Reserve finds itself: stuffed with assets of uncertain value and uncertain liquidity. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities are liquid now, but only because the market knows that the Fed stands as the buyer of last resort. What would happen to the liquidity of those markets if the Fed became the seller of first resort? The question answers itself. The Fed cannot sell its assets to support the dollar against sustained market selling. The government may do so through capital controls (and it will implement them, first soft, then hard), but the currency is then stabilised at the expense of collapsing trade and living standards, either through domestic inflation or shortages.

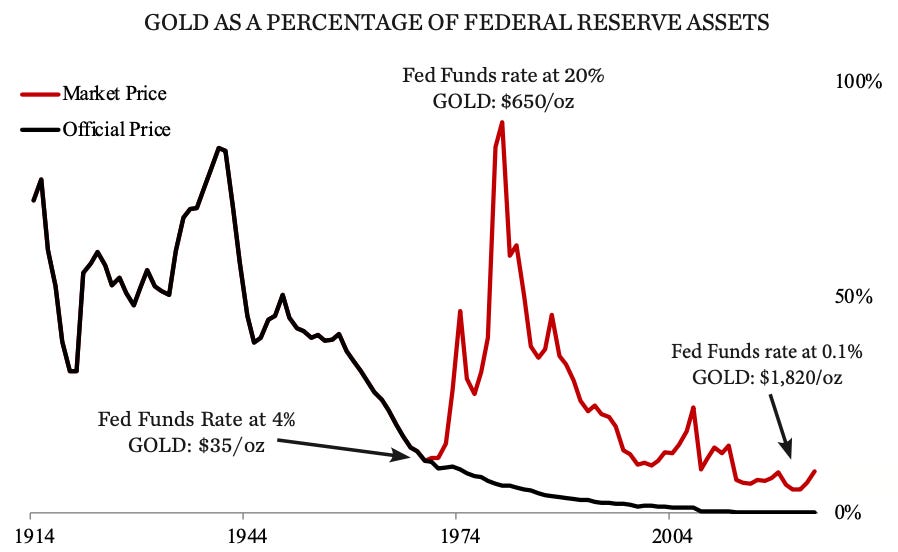

The Federal Reserve’s position is untenable because over time markets are more powerful than politicians and bureaucrats, and markets force balance sheets to balance, as is illustrated by the chart below. The black line shows the Fed’s gold position as a percentage of its liabilities at the official government price, which was $20.67/oz from 1913 to 1934, then $35/oz, until it was repegged at $38/oz under the 1971 Smithsonian Agreement, and finally set to the current, official price of $42.22 in 1973. The market is not fooled by official prices, of course: the red line shows the Fed’s gold position using market prices.

Note that when interest rates are low and falling, the Fed’s bond portfolio is richly priced, meaning the market prices the Fed’s gold position at a low price, as in 1968. Conversely, when rates are high and rising, and the value of the Fed’s bond portfolio is crashing, gold must soar in price in order to keep the Fed’s balance sheet balanced, as in 1980. Interest rates fell from 1980 until three years ago, and the chart shows that gold, as a percentage of the Fed’s balance sheet, fell until the COVID credit blitz in 2021. The reading at the end of 2021 was gold at 5.5% of the Fed’s assets, less than half of the 1969 bottom of 12.2%. This makes sense: the bubble by the 2020s was far larger than that of the 1960s.

Rates have been rising since 2022, and (consistent with the thesis of Gryning Essay’s) gold as a percentage of the Fed’s balance sheet has also been rising. Note that the nominal increases have been somewhat muted because the Fed’s balance sheet has also been shrinking. Nevertheless, at a current value of 11% of the Fed’s balance sheet, even at record nominal prices gold is still cheaper than it was in 1969, at the beginning of that epic bull market.

Our theory is based on sound market principles, and the historical data fits the theory well. But there is a problem. The analysis is the best case because it assumes that the Fed actually owns the 8,133 tons of gold on its balance sheet. And that is almost but not quite true.

Congress chartered the Fed in 1913 to issue a flexible national currency. The previous regime had allowed nationally chartered banks to issue Treasury notes, which were required to be backed by a like quantity of Treasury bonds. The supply of U.S. currency, therefore, reflected the size of federal debt. As critic Paul Warburg pointed out: “If the Panama Canal costs $500,000,000 we shall have $500,000,000 additional currency, whether the nation needs it or not. But what sane reason can be found to make the currency of the nation dependent on whether or not we build a canal?”

Warburg was the chief architect of the Federal Reserve, and he designed it to issue money in accordance to the needs of business, not the desires of government. But, as a brake, to make sure that the Fed did not overissue, it was required to hold 40% worth of gold against the currency it issued and 35% against banks’ required reserves held at the Fed.

In 1929, the largest theretofore credit bubble in history popped, and in 1934, Franklin Roosevelt signed a decree making the possession of gold a felony. Americans were required to hand in their gold bullion or face a “$10,000 fine or 10 years imprisonment, or both.” The Federal Reserve was similarly required to hand over its gold to the Treasury, but, unlike the citizens, who received $20.67 per ounce in Federal Reserve notes, the Federal Reserve itself was issued gold certificates equal to the amount of gold seized. When Roosevelt revalued gold to $35/oz, the citizens were cheated, but the Federal Reserve’s gold certificates were revalued higher. Since the Federal Reserve’s money- creation capacity was legally constrained by the gold coverage legislation, revaluing the gold certificates meant the Fed could issue more money and credit.

This loosening of constraints on the Fed had no immediate effect. The ongoing depression meant there was little demand for credit, and political and economic turmoil in Europe sent gold into the U.S. for safety. The Fed’s gold coverage was 61% in 1934 and reached 85% by 1940.

It was not to last. Enormous war spending doubled the Fed’s balance sheet over five years even as the Fed’s reported gold holdings fell by 10%. As a result, by 1945, the Fed’s gold coverage had fallen to only 40%, the statutory requirement for currency. So, Congress passed legislation reducing the coverage requirement to 25% for both money and member bank reserves. So much for Warburg’s gold constraint.

The government grew modestly under Eisenhower, but then Keynes’s disciples grabbed control under Kennedy. Their policies were based on a study by A.W.H. Phillips that showed that from 1861 to 1957, inflation and employment had been correlated. This was a period that had operated under gold standards of various guises, and so it should have been no surprise that inflation caused by credit bubbles resulted in high levels of employment, whereas the deflationary crashes resulted in soaring unemployment.

But the Keynesians mistook the Phillips curve as a policy lever—as if there were a permanent, stable relationship between unemployment and increases in prices, irrespective of whether those increases were driven by credit inflation or monetary debasement. According to the new economists, politicians had no choice but to select where along the Phillips curve society should travel by modifying the amount of deficit spending.

Kennedy and Johnson were delighted to discover that the best way to aid the working man was through deficits: spending soared by 65 percent under their watch, and more than half of the resulting deficit was monetised by the Federal Reserve. Proliferating Treasury securities acted as reserves in the banking system to allow money and credit to increase at a ferocious pace, while increasingly nervous foreign central banks accelerated their redemptions of dollars into gold.

By March 1965, the Fed’s gold cover had fallen to 25.01%, just above the statutory limit. Congress decided it could not accept the gold brake that Warburg had included in his design, so it voted to abolish the gold coverage requirement against member bank reserves, allowing all of the remaining gold to back just the currency. According to a 1968 Federal Reserve commentary, “The 1965 Act freed over $4 billion of gold [from acting as reserves] and the free gold supply accordingly jumped up to nearly $6 billion.”

The gold lasted only three more years: foreign redemptions and Johnson’s excessive spending sent the remaining gold cover below 25% even for just federal reserve notes. On March 19, 1968, Johnson signed a bill abolishing any kind of gold coverage requirements. Fed chairman William McChesney Martin hailed the move because it “would make absolutely clear that the United States’ gold stock is fully available to serve its primary purpose as an international reserve,” domestic savers been damned. Foreign central banks availed themselves of that availability until August 15, 1971, when Nixon announced to the world: “I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend, temporarily, the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets.”

Nixon may have actually believed that the suspension of convertibility was temporary (there had been many such banking system suspensions in U.S. history, all of which had been temporary). Attempting to revive the Bretton Woods system, the U.S. revalued its gold first to $38/oz in 1972 and then $42.22/oz in 1973.

According to a 1974 Federal Reserve commentary, the practical effect of the revaluation was this:

the value of the Treasury’s gold increased by $800 million in nominal terms,

the Treasury issued to the Fed an additional $800 million worth of gold certificates and received in exchange an increase in the Treasury’s deposit account at the Fed by a like amount,

the Treasury then spent that $800 million into the economy, which

thereby increased the monetary base by $800 million.

The article observed:

The Treasury was able to pay for $800 million of goods and services without using tax revenues or putting additional upward pressures on market interest rates by increasing the stock of Government securities held by the public. However, this does not mean that the Government sector was able to acquire goods without any effects on the real disposable income of consumers. Since the effect on the monetary base was not offset by Federal Reserve actions, there was a resulting expansion of the money stock, an expansion of total demand, and ultimately upward pressures on prices.... The Treasury now had an alternative means, in addition to using tax revenues or the proceeds from the sale of Government securities, to finance its planned expenditures.

Note that the 1968 Fed commentary quoted above interpreted a relaxation or abolishment of the gold coverage requirement as allowing the private banking system to increase money and credit, whereas the 1974 commentary explained that the increase in the official price of gold allows the Treasury to create money ex nihilo to drive the monetary base and inflation higher.

This relationship between the Fed and the U.S. gold is uncharacteristic of normal central banking practice. In Europe, for example, central banks own their gold directly and have threatened to revalue it to recoup losses suffered from following Bernanke’s and Powell’s policies of bailing out insolvent banks. In March 2023, Joachim Wuermeling, a member of the executive board of the Bundesbank, stated in a press conference:

The most important revaluation item of course is the reserve for the 3,355 tonnes of gold. In fact, the value is about €180 billion euros above the cost of purchasing it, so this is a reserve for us, and it’s part of the considerable own-funds of Bundesbank, underlining the soundness which the President mentioned. So, in fact, it’s on firm ground—the balance sheet of Deutsche Bundesbank—and this certainly makes it easier for us to bare losses over a certain period of time.

Calling the Bundesbank’s balance sheet sound because gold has risen in nominal price clearly indicates that Joachim does not understand that the more the central banks print, the more their currencies fall, and the higher the gold price goes to keep the central bank’s balance sheet always in balance—he and other central bankers seem to imagine that the gold price increase is unrelated to monetary policy, manna from heaven, that just happens, fortuitously, to plug the holes in their balance sheets.

Investing by Design is a systematic framework for seeing what others miss and making confident choices under pressure. Built for analytical minds who hate fuzzy thinking. In an age where most investors get their “insight” from headlines, we prefer something a little more… robust.

The U.S. analysis is more complicated because its central bank does not own the gold. Powell recently confirmed this in a letter to Congress dated February 23, 2024: “The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) provides gold custody on behalf of certain official-sector account holders, which include the U.S. government, foreign governments, other central banks, and official international organizations. The FRBNY does not own any of the gold it holds as custodian, and no other part of the Federal Reserve System owns gold. . . .”

Powell may not be quite right for two reasons. First, the Treasury publishes the quantity of the 8,133 tons of gold that each of its eight depositories holds and also lists the nominal value of $11,041 million (valued at $42.22/oz). According to the Treasury, the Fed custodies only 5% of the Treasury’s physical gold, but the Fed lists the full nominal value on its balance sheet as an asset, which means that all of the Treasury’s gold is encumbered by the Fed. Indeed, the 1974 Fed commentator wrote: “Meanwhile, the increased value of the gold stock became a 100 percent backing for the gold certificates which the Treasury issued to the Federal Reserve.” Presumably the “backing” means that the Fed has some derivative claim on the gold, though perhaps only in the nominal amount of $11 billion.

The second point is more nuanced and is answered by the question: does the market care that the Fed’s and the Treasury’s balance sheets are legally distinct? In the 1960s, the Treasury conspired with seven European countries to smash the gold price whenever it peaked above the official price of $35/oz, essentially using the Treasury’s gold to protect the value of the Federal Reserve note, colloquially known as “the dollar.” The Treasury did the same thing unilaterally in the 1970s (the Assistant Secretary of State for Economic Affairs told Henry Kissinger and Ken Rush in 1974: “I think we should look very hard then, Ken, at very substantial sales of gold—U.S. gold on the market—to raid the gold market once and for all”).

Treasury bonds are the global reserve asset, they give the U.S. an enormous subsidy, they are the foundation of the American empire, and they mature into Federal Reserve notes. The government will not willingly allow the Fed to collapse: in attacking the Fed, the market must consider the Treasury’s gold, whatever the legal distinction between the Treasury’s and the Fed’s balance sheets.

Just because the Treasury will instinctively defend the Fed does not mean it will not eventually surrender to the market, however. Indeed, if defending the Fed allows Congress to continue its profligate spending, then (like the Gold Pool and the 1970s) the Treasury’s efforts will unleash the financial forces that will overwhelm it. This is when the legal distinction between Fed and Treasury and owning gold versus owning a claim on gold will manifest. The U.S. has already allowed two previous central banks to dissolve; why not shutter a third if supporting it becomes too costly to maintain?

And what a wonderfully populist move it would be to allow the Fed to fail: the U.S. could issue currency directly in the form of gold-backed Treasury notes and allow the Federal Reserve note to disappear. The indebted will be relieved, obligations to foreigners will be wiped out, wealth will be redistributed toward the productive and away from legacy holders of claims on assets, and the debt system that enriched the few will disintegrate, a modern jubilee. This is more or less what an uncontrolled unwind of the dollar system would look like. Perhaps not a terrible outcome for a populist like Trump, though it would come with much risk and collateral damage, such as the end of the U.S. empire and exorbitant privileges.

Current market chatter is that the Trump administration may attempt a controlled devaluation instead. The specific policies to accomplish this are presented in a November 2024 paper written by Stephen Miran, whom Trump has nominated to be the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers: “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System.” (click here)

Miran embraces the “Triffin dilemma” in which “the reserve asset producer must run persistent current account deficits as the flip side of exporting reserve assets. . . . As the rest of the world grows, the consequences for U.S. export sectors—an overvalued dollar incentivising imports—become more difficult to bear, and the pain inflicted on that portion of the economy increases. . . . Eventually (in theory), a Triffin ‘tipping point’ is reached at which such deficits grow large enough to induce credit risk in the reserve asset. The reserve country may lose reserve status, ushering in a wave of global instability.”

In order to rebalance trade, Miran first cites studies suggesting that tariffs up to 20% creates net income for the imposing country: either the foreign currency falls, in which case domestic prices are stable and consumers do not change their behavior, but the Treasury gets the tariff income, or the foreign currency does not adjust, in which case there is inflation for imported goods but also an incentive to reshore manufacturing. The benefits disappear if the other county retaliates, but Miran points out that existing, enormous U.S. trade deficits mean other countries have much more to lose in a trade war.

If the dollar is already too strong and tariffs threaten to raise the dollar’s value further, then Trump must also weaken the dollar but in a way that does not raise interest rates or increase financial instability. Miran has several suggestions:

One way of doing this is to impose a user fee on foreign official holders of Treasury securities, for instance withholding a portion of interest payments on those holdings. Reserve holders impose a burden on the American export sector, and withholding a portion of interest payments can help recoup some of that cost. Some bondholders may accuse the United States of defaulting on its debt, but the reality is that most governments tax interest income, and the U.S. already taxes domestic holders of UST securities on their interest payments. While this policy works through currencies as a means of affecting economic conditions, it is actually a policy targeting reserve accumulation and not a formal currency policy. . . . As in tariffs, [Trump should] differentiate among countries. Presumably the Administration would want to withhold remittances to geopolitical adversaries like China more severely than to allies, or to countries that engage in currency manipulation more severely than to those that do not. The Administration would likely want to give our allies the benefits of reserve currency usage, not our adversaries.

He also cites the writings of Fed guru Zoltan Poszar, whose policy expectations rest on the following three assumptions:

1) security zones are a public good, and countries on the inside must fund it by buying Treasurys;

2) security zones are a capital good; they are best funded by century bonds, not short-term bills;

3) security zones have barbed wires: unless you swap your bills for bonds, tariffs will keep you out.

Miran thus suggests: “An agreement whereby our trading partners term out their reserve holdings into ultralong duration UST securities will; a) alleviate funding pressure on the Treasury and reduce the amount of duration Treasury needs to sell into the market; b) improve debt sustainability by reducing the amount of debt that will need to be rolled over at higher rates as the budget deteriorates over time; c) solidify that our provision of a defense umbrella and reserve assets are intertwined. There may even be arguments for selling perpetuals rather than century bonds, in this eventuality.”

Why would U.S. allies agree to this? “First, there is the stick of tariffs. Second, there is the carrot of the defense umbrella and the risk of losing it. Third, there are ample central bank tools available to help provide liquidity in the face of higher interest rate risk. . . . This mark-to-market risk of holding longer-term debt can be mitigated via swap lines with the Federal Reserve, or alternatively, with the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilisation Fund. Either institution can lend dollars to reserve holders at par against their long-term Treasury debt holdings, as a perk of being inside the Mar-a-Lago Accord,” as was done to save the banking system following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. In other words, the Fed would simply print any losses due to interest rate risk.

All of this makes geopolitical sense. The post-World War II institutions are not apples with a few worms inside but simply “balls of worms,” to use Elon Musk’s colorful metaphor. Trump understands that the international order is dead, that the world is returning to spheres of influence. This is why he will likely cede Ukraine to Russia even as he seizes Greenland and Panama; it makes sense under this worldview to demarcate friend, neutral, and enemy in the financial markets.

For his part, Trump’s newly minted Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent gave a speech last June outlining his vision when angling for the job: “We’re also at a unique moment geopolitically, and I could see in the next few years that we are going to have to have some kind of a grand global economic reordering, something on the equivalent of a new Bretton Woods or if you want to go back like something back to the Steel Agreements [which led to the European Common Market and then the European Union] or the Treaty of Versailles, there’s a very good chance that we are going to have to have that over the next four years, and I’d like to be a part of it.”

One topic that Bessent and Miran have avoided discussing is gold revaluation. Recall that the Federal Reserve’s 1974 commentary described how a revaluation grants the Treasury spending power ex nihilo, without increasing taxes or putting upwards pressure on interest rates but at the cost of a weaker dollar—in other words, it achieves all three of Trump’s objectives. The problem is that Congress, not Bessent, sets the official price.

Miran did have this to say about gold:

The Gold Reserve Act also authorizes the Secretary to sell gold in a way “the Secretary considers most advantageous to the public interest,” providing additional potential funds for building foreign exchange reserves. However, the Secretary is statutorily required to use the proceeds from such sales “for the sole purpose of reducing the national debt.” This requirement can be reconciled with the goal of building foreign exchange reserves by having the ESF sell dollars forward. If gold sales are used to deliver dollars into the forward contracts, it will likely satisfy the statutory requirement of reducing national debt.

Miran has the Treasury selling gold to buy non-U.S. sovereign debt as a way to weaken the dollar, but the sale proceeds could be used to fund anything, including investments to subsidise rebuilding U.S. manufacturing. Note as well that his suggested mechanism neuters the Congressional power to set the official price of gold as well as functionally avoids the debt-repayment restriction of the Gold Reserve Act, though it would require the debt ceiling to be raised.

Adding to speculation that the U.S. executive branch might mobilise the nation’s gold reserve, Bessent offered these cryptic remarks from the Oval Office on February 3: “Within the next twelve months, we’re going to monetise the asset side of the U.S. balance sheet for the American people. We’re going to put the assets to work. . . . It’s going to be a combination of liquid assets, assets that we have in this country, as we work to bring them out to the American people.”

It is not clear what exactly Bessent meant, but on February 6, the Financial Times published an article titled: “Gold glitters as the unimaginable becomes imaginable”: “Some hedge fund contemporaries of Scott Bessent, the hedgie-turned-US Treasury secretary, are speculating about a revaluation of America’s gold stocks. . . . Knowledgeable observers reckon that if these were marked at current values—$2,800 an ounce—this could inject $800bn into the Treasury General Account, via a repurchase agreement.”

The point of this commentary is not that I agree or disagree with Miran’s economic theories or that I am predicting that Bessent will execute a sudden gold revaluation. Indeed, Miran himself recommended an extended timeline:

There is good reason to be more cautious with changes to dollar policy than with changes to tariffs.

Steps to strengthen undervalued currencies will likely not be taken until risks can be mitigated. The Administration will likely wait for more confidence that inflation and deficits are lower, to limit potentially harmful increases in long yields that could accompany a change to dollar policy. Waiting for turnover at the Federal Reserve [Powell’s term as chairman ends May 15, 2026] increases the likelihood that the Fed will voluntarily cooperate to help accommodate changes in currency policy.

Tariffs are a tool for negotiating leverage as much as for revenue and fairness. Tariffs will likely precede any shift to soft dollar policy that requires cooperation from trade partners for implementation, since the terms of any agreement will be more beneficial if the United States has more negotiating leverage.

Traders seems to be less cautious, with bullion prices surging in response to established media publications like the Financial Times raising the prospect of gold revaluation as a follow up to its article on January 29 titled “Gold stockpiling in New York leads to London shortage,” a phenomenon that has become more intense since the article was published. It may, in fact, serve Trump’s interest to delay and leak hints about gold because the higher the gold price goes, the more money the Treasury will be able to create on a sale, swap, or revaluation.

Heretofore the only institution that mattered with regards to dollar strength was the Federal Reserve; Trump has shifted all attention to the Treasury Department. No one cares about Powell any more. There is increasing evidence that Bessent and Trump are going to remake the financial system and that gold is going to play a role. The BRICS are already moving in that direction.

In 2012, Bernanke lectured that there was not enough gold to balance international trade—he was wrong; of course there is, at the correct price, a number very much larger than $2,900 per ounce.

thank you for a very comprehensive discussion of this subject which has become far more popular of late. and of course, your last line, "at the right price" is what everyone is trying to imagine, at least the gold bugs out there!!