US stocks experienced a severe sell-off on Monday as fears of a US recession intensified.

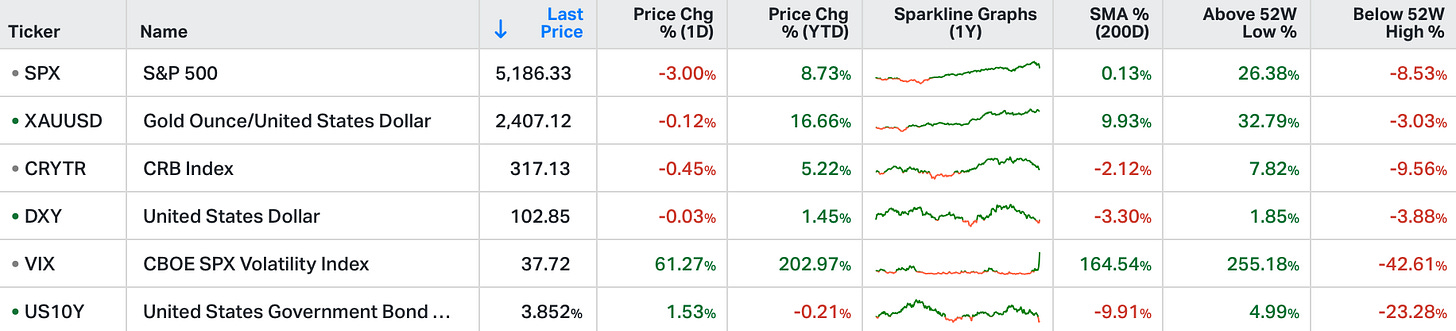

The S&P 500 dropped 3%, while the Dow Jones plummeted by 1,033 points.

Wall Street's fear gauge, the CBOE Volatility Index, surged to its highest level since October 2020.

Adding to the negative sentiment were weaker-than-expected earnings from leading tech companies and growing uncertainty in the AI sector.

Nvidia’s (-7.1%), Microsoft (-3.3%), Apple (-5%), Amazon (-4.4%), Meta (-2.5%), Alphabet (-4.5%), Tesla (-4.2%), Broadcom (-1.1%) and Qualcomm (-0.5%) were all in the red.

In the past couple of weeks, we've been looking at this chart of the Nikkei (Japanese stocks) and the Japanese yen.

As we discussed, with the Bank of Japan recently announcing plans to exit its role as the global liquidity provider while the Fed simultaneously holding interest rates in the most important global economy at historically tight levels, it raises the risk of a liquidity shock for global markets.

The first stage is a reversal of the "carry trade" - where global investors borrowed yen for (effectively) free, converting that yen to dollars (USDJPY goes up), and investing those dollars in the highest quality dollar-denominated assets (U.S. Treasuries and the big tech oligopoly stocks).

That unwind is being represented in the chart above, and the chart below …

And as you can see, it has resulted in trend breaks in major global stock markets. Bond markets, too. And the severity of these market moves are historically extreme.

If we look at the three day loss in the Nikkei (Japanese stocks), it's comparable to only three other dates over the past thirty years.

Clearly these are not friendly comparables - in fact, in each case a central bank response (i.e. QE) shortly followed.

That leads us the second stage of the carry trade unwind.

With the occurrence of rare/low probability market moves, the possibility of margin calls and forced liquidations rises in the financial sector. And that can quickly spread, and lead to a liquidity shock and global financial instability.

With that, is the recent pressure on markets over? Unlikely.

To this point, surprisingly, the Fed has yet to even signal that the policy outlook has materially changed, despite the recent weak labour data and despite the market activity of the past two days.

That said, remember Jerome Powell admitted last week that they have "a lot of room to respond" to a shock or weakness in the economy (i.e. plenty of rate cut ammunition, given the high level of the policy rate) - and the Fed and other central banks have made it explicitly clear, over the past several years, that the balance sheet is now a tool used to fix "financial dislocations."

They break it. And they fix it.

In fact, Fed member Austan Goolsbee said it yesterday: "If the economy deteriorates, the Fed will fix it."

On that note, as we've discussed many times here in my daily notes, we've yet to see an example of a successful exit of QE. It's Hotel California - "you can check out, but you can never leave."

I’m pretty sure they didn’t think it through when Bernanke started it