This week, we focus on the immediate impacts of the recent US-China trade escalation.

US and China cargo trade

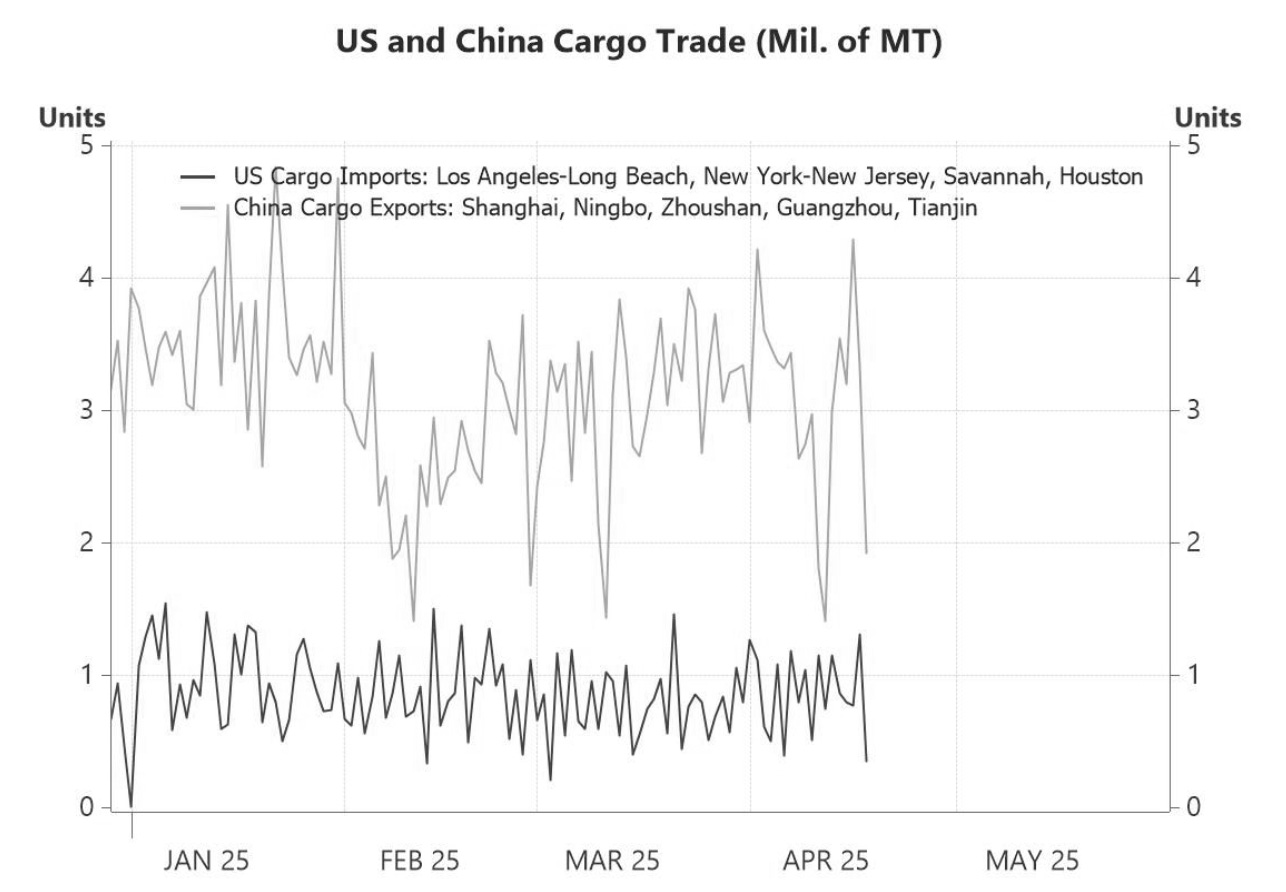

Financial markets have recently found some reason for relief, as both the US and China appear to be lowering the temperature on further trade tariff actions. Recent messaging has leaned more toward a de-escalation of trade tensions, though concrete details remain sparse, and it is unclear how or when formal negotiations might begin. That said, the substantial and mutually imposed tariffs between the US and China remain firmly in place, and a significant rollback does not seem likely in the near term. In the meantime the economic impact of these tariffs is beginning to surface in the data, as shown in charts 1 to 3. Chart 1, based on IMF estimates, shows a sharp decline in daily activity at several key ports involved in US-China trade. However, while the drop is notable, port activity still remains within historical ranges, so a more fundamental shift is not yet evident.

US-China freight rates

Another indication of the impact of escalating US-China tensions is seen in global freight rates, as shown in chart 2. Freight costs on routes from Shanghai to New York and Los Angeles have dropped sharply—even before the most recent round of trade escalations—likely due to growing caution among shippers about what trade actions might come next for China. This decline contrasts with the year-end spike in shipping rates in 2024, which likely reflected front-loading of shipments in anticipation of potential US tariffs. Looking ahead, the outlook remains uncertain and potentially discouraging, especially following recent reports of widespread shipment cancellations from China to the US. These developments suggest that China-to-US shipping volumes may remain subdued or decline further over the near-term.

Trade indications from South Korea

A perhaps firmer indication comes from South Korea’s trade figures for the first 20 days of April, widely regarded as an early signal of global trade trends. The data showed a notable slump compared to the same period last year, driven largely by a sharp drop in shipments to the United States. This move has made US-China trade increasingly difficult, aside from a few exemptions on key goods such as electronics and semiconductors. Even so, South Korea’s semiconductor export growth continued to slow in April, highlighting the broader fallout from ongoing trade tensions. More definitive trade data from South Korea are expected later this week.

Broader topics on China

Next, we turn to broader structural trends in China’s economy, starting with chart 4, which depicts China’s financial balances based on its flow of funds accounts. Over the past decade, the general government has accumulated an increasingly large net deficit, as its sources of funds (liabilities) have consistently outpaced the uses of funds (assets). This has fuelled growing investor concerns over government indebtedness. In contrast, the private sector—particularly households—has seen a sharp rise in its net surplus, almost mirroring the government’s deterioration. Meanwhile, the foreign sector has continued to run net deficits with China, consistent with China maintaining a current account surplus with the rest of the world. That said, unlike in the 2000s and early 2010s—when private and foreign sector balances often moved closely together—recent shifts in the general government and private sector balances appear to have had a more limited effect on the foreign sector's position.

The US’ current account deficit

Expanding on these themes, chart 5 highlights the persistent current account deficits of the US alongside the cumulative current account surpluses of its major trading partners. Some may advocate for reducing US imports—such as through tariffs, as President Trump is currently pursuing—as a way to close the current account deficit. However, such measures tend to address only the symptoms rather than the root causes. This topic featured prominently in client meetings in Singapore. Fundamentally, the persistent current account deficit in the US can be seen as a structural outcome of the dollar’s role as the world’s primary reserve currency. The global demand for dollar-denominated assets drives sustained financial inflows into the US, which, by balance of payments accounting, necessitates a corresponding current account deficit.

What China Plus One?

Lastly, we turn to the China Plus One strategy, a diversification approach adopted by firms and governments since US-China tensions began during Trump’s first term in 2018. However, even this approach may no longer offer a full hedge against additional US trade actions. As chart 6 shows, the shift away from China has contributed to a sharp rise in the US trade deficit with several alternative partners, particularly Asian economies such as Vietnam. In light of the broader scope of US trade actions—exemplified by Trump’s recent “Liberation Day” tariffs—businesses are being forced to rethink their global strategies. Some may find themselves needing to reshore production to the US, despite the fact that labour cost advantages, technical know-how, and manufacturing infrastructure for many goods remain more competitive abroad.